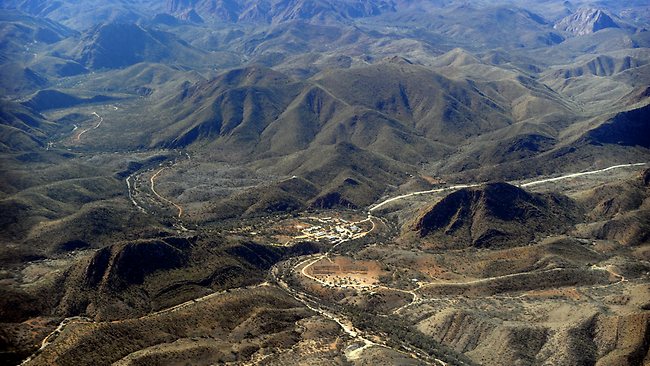

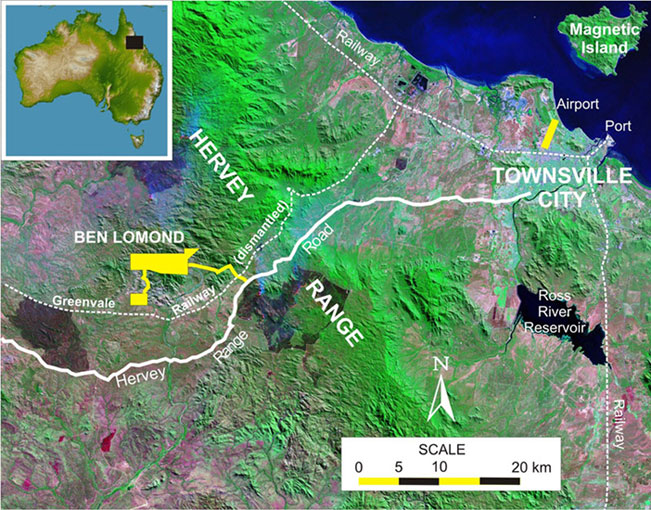

Rum Jungle is about 64 kilometres south of Darwin in the Northern Territory, among the headwaters of the East Finniss River.

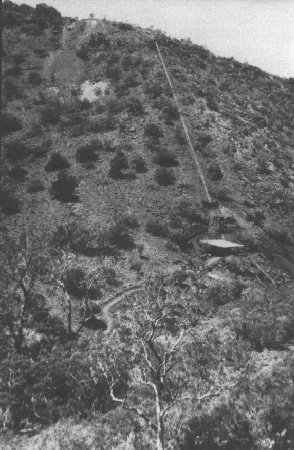

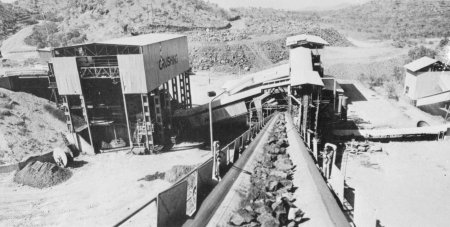

The Rum Jungle mining project operated from 1954 to 1971. Processing of uranium and copper continued from stockpiles until April 1971 although uranium ore had last been extracted in 1963.

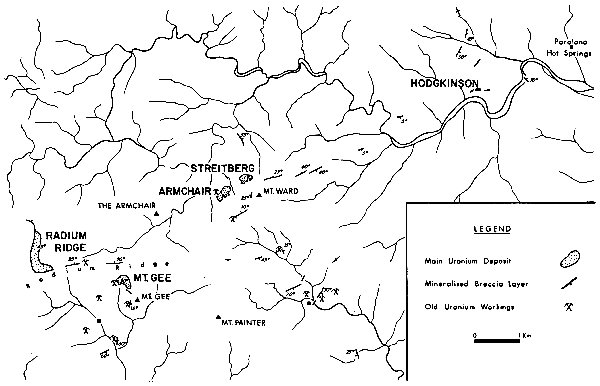

A total of 863,000 tonnes of uranium ore were processed, the average grade was 0.28-0.41%, and 3,520 tonnes of U3O8 were produced from various Rum Jungle deposits − White’s (U-Cu-Pb), Dyson’s (U), Rum Jungle Creek South (U), and Mt Burton (U-Cu).

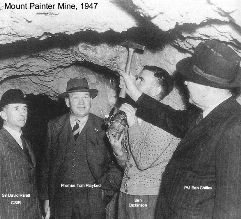

HISTORY

Uranium and copper mineralisation was discovered in the Rum Jungle area in 1869 by Goyder’s survey party, but it was not recognised as such until 1949. In April 1948 an announcement in the Commonwealth Gazette stated that rewards would be paid for the discovery of uranium in Australia and its territories. The maximum amount of the reward was fixed at £25,000. Time Magazine reported on 15 September 1952:

From Darwin to Melbourne, the word had got around that Australia’s vast, tropical Northern Territory was bursting with uranium. Hundreds of adventurous young men from Australia’s overcrowded southern cities, plus many an old gold fossicker from West Australia, were making their way up through the desert by jeeps, horse-drawn wagons, on horseback, even in airplanes. In Darwin, Geiger counters were sold out as fast as they came into the store. One newspaper advertised counters: “Find Uranium and Make Your Fortune.” The excitement had begun at Rum Jungle, 60 miles south of Darwin, where a prospector named Jack White uncovered a three-mile-long lode of uranium-bearing ore in 1949.

In March 1952, representatives of the United States Atomic Energy Commission (USAEC) and of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) visited Australia to discuss, among other things, the development of the Rum Jungle uranium field. This led to the provision of funds to develop the Rum Jungle project by the Combined Development Agency and the signing of an exclusive supply contract between the Commonwealth and the CDA. The uranium produced between the commencement of production in 1954 and January 1963 was used to fill the supply contract with the CDA for use in nuclear weapons.

The Commonwealth entered into a contract with the Consolidated Zinc Group in August 1952 to develop and operate the Rum Jungle project. In the same year Consolidated Zinc formed a wholly-owned subsidiary, Territory Enterprises Pty Ltd (TEP) to manage all aspects of the operation including exploration, mining and milling. (In 1962, Consolidated Zinc merged with the Rio Tinto Mining Company of Australia Ltd to form Conzinc Riotinto of Australia Ltd or CRA.)

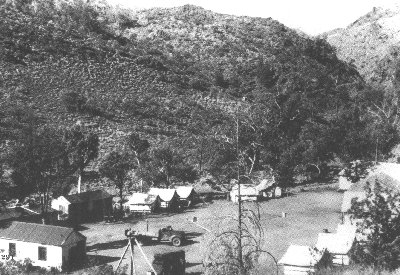

The town of Batchelor was redeveloped to service the mine. Batchelor became a booming township with a power station, acres of suburban homes, a hotel, a community centre, and a population of 500. Many workers lived in seriously sub-standard conditions. In 1956, a Melbourne newspaper ran a front-page story describing the conditions at the “Rum Jungle Hell Hole”. Security at the mine site was tokenistic.

In addition to supplying the CDA, some uranium was put on the open market, and some uranium was stored at Lucas Heights in southern Sydney. About 2,000 tonnes of yellowcake was stockpiled by the time the mine closed in 1971. In 1994, 239 tonnes of Rum Jungle uranium oxide were sold to a US utility, leaving 1814 tonnes still stockpiled. The remainder was sold in subsequent years.

Uranium ore from other deposits − including the Eva deposit near the Queensland border, and Adelaide River − was processed at Rum Jungle.

ENVIRONMENTAL MISMANAGEMENT

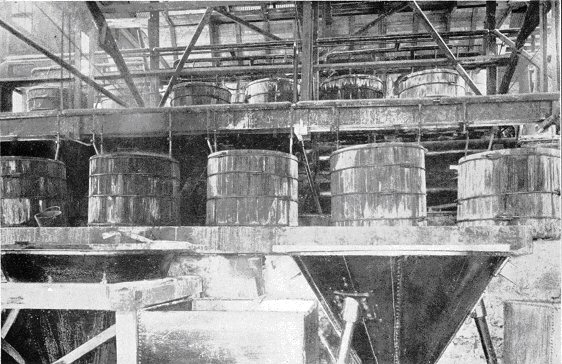

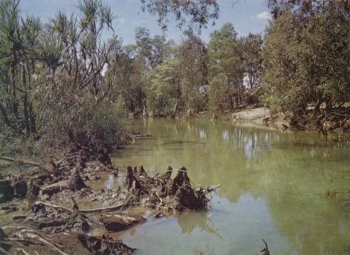

From the start of processing operations in 1954, the discharge of tailings was unconstrained and the solids settled out, while the acidic supernatant liquors drained into ‘Old Tailings Creek’ and thence to the East Branch of the Finniss River, 0.8 km to the west. Barren liquors from copper launders constructed between the plant site and the Old Tailings Dam also flowed into the East Branch via Old Tailings Creek.

Thus in the early period of operation, there was not even a dam wall to contain the tailings, which were simply discharged onto a flat plain and allowed to drain into the river. Successive walls were then built and washed away by floods until, in 1961, the tailings were discharged into disused (but presumably quite porous) open-cuts rather than onto the flat plain.

The tailings were redirected to Dyson’s Open Cut in 1961, the copper launders were relocated from the Old Tailings Dam area to a site adjacent to Dyson’s Open Cut, and a system of controlled discharges was introduced. Under this system, spent process liquors were collected during the Dry Season, in two dams fitted with sluices that were constructed across the East Branch of the Finniss River. With the onset of the Wet Season, fresh water entered both these dams and a relatively unpolluted tributary which was also dammed (called the Sweet Water Dam). When the river flooded, all dams were breached, releasing water to the East Branch through the diversion channel and White’s Open Cut. At that time, it was considered that this procedure would provide sufficient dilution to allow safe discharge of water. More recent calculations have shown that the policy of “safe dilution” could not have worked.

The practice was abandoned between 1965 and 1968 when tailings were directed to White’s Open Cut, the walls in the riverbed were breached, spent process liquor (called raffinate) was directed either to the copper heap leach site or directly to White’s Open Cut, and partial recycling of raffinate commenced in the treatment plant. This method of effluent disposal continued until operations ceased in 1971.

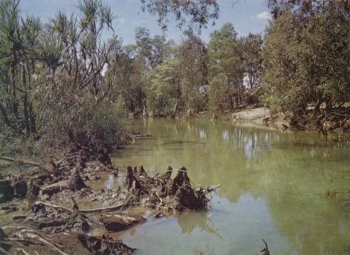

The 1970 report of a Senate Select Committee on Water Pollution said: “One of the major pollution problems in the Northern Territory is that caused by copper and uranium mining at Rum Jungle. The strongly acidic effluent from the treatment plant flows via the East Finniss River into the Finniss River, making the water unsuitable for either stock or human consumption for a distance of 20 river miles. Vegetation on the river banks has been destroyed and it will be many years before this area can sustain growth.”

The mining company Conzinc (now part of the Rio Tinto Group) has consistently denied any responsibility for rehabilitation.

The Australian Atomic Energy Commission, the Commonwealth government nuclear agency based at Lucas Heights, lied about the extent of the environmental damage at Rum Jungle, obfuscated, and refused to release relevant information to other government bodies (see SEA-US and The Age 1/12/76).

The saga also reveals complicity between government and companies. In June 1971, Mr R. E. Felgenner, First Assistant Secretary, Northern Territory Economic Affairs, presented to his Minister a submission in which he sought approval to investigate the situation at Rum Jungle. In the submission he said: “Early in 1962 the Minister for Territories informed the Minister for National Development that, while the source of pollution has been established beyond doubt and constituted an offence against the provisions of the Control of Waters Ordinance, he was reluctant to proceed against the companies for reasons of their association with the Commonwealth in the venture.”

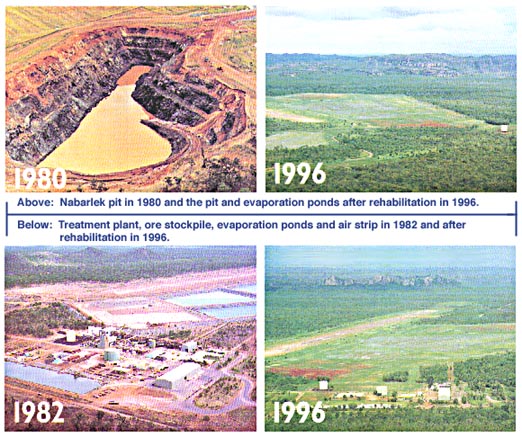

REHABILITATION AND RECREATION

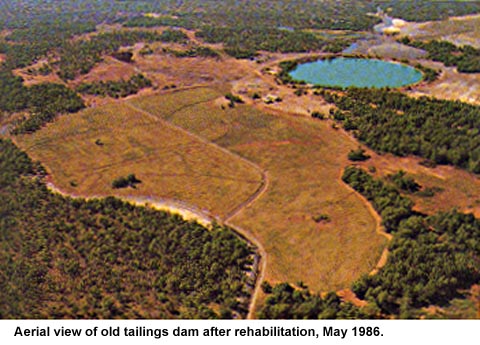

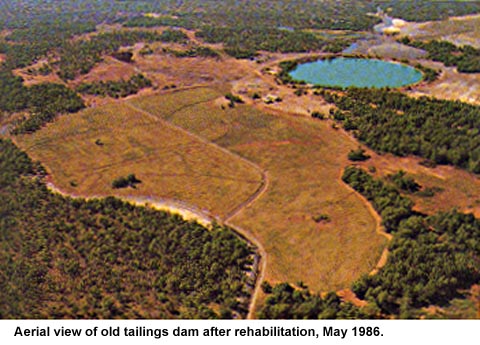

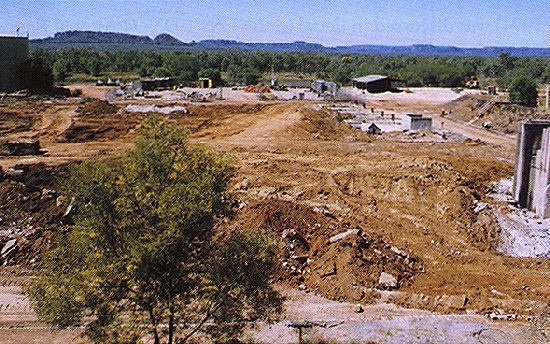

An initial attempt to clean up Rum Jungle was made in 1977, which led to the setting up of a working group to examine more comprehensive rehabilitation. A $16.2 million Commonwealth-funded program got under way in 1983-88. A supplementary $1.8 million program to improve Rum Jungle Creek South waste dumps was undertaken in 1990-91.

One of the principal problems associated with rehabilitating the Rum Jungle Creek South (RJCS) open cut was that the area was converted to a lake after mining ceased, and as the only crocodile-free water body in the Darwin region, the site quickly became very popular with locals and Darwin residents as a recreation reserve. The mine area was characterised by high external gamma levels, alpha-radioactive dust and significant levels of radon daughters in prevailing air. It is known that the rates of radioactivity in the area were much higher after mining than before. Based on these post-mining radiation levels, it had been estimated that annual doses of some individuals were about 5 millisieverts (mSv), the Australian limit for public exposure up until the late 1980s. As the new limit was about to be dropped to 1 mSv per year, rehabilitation was required. As a result, a supplementary $1.8 million program to improve Rum Jungle Creek South waste dumps was undertaken in 1990.

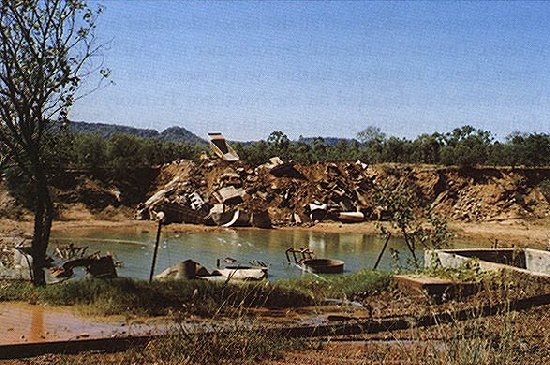

In 2003, a government survey of the tailings piles at Rum Jungle found that capping which was supposed to help contain radioactive waste for at least 100 years had failed in less than 20 years. The Territory and Federal Governments continued to argue over responsibility for funding rehabilitation.

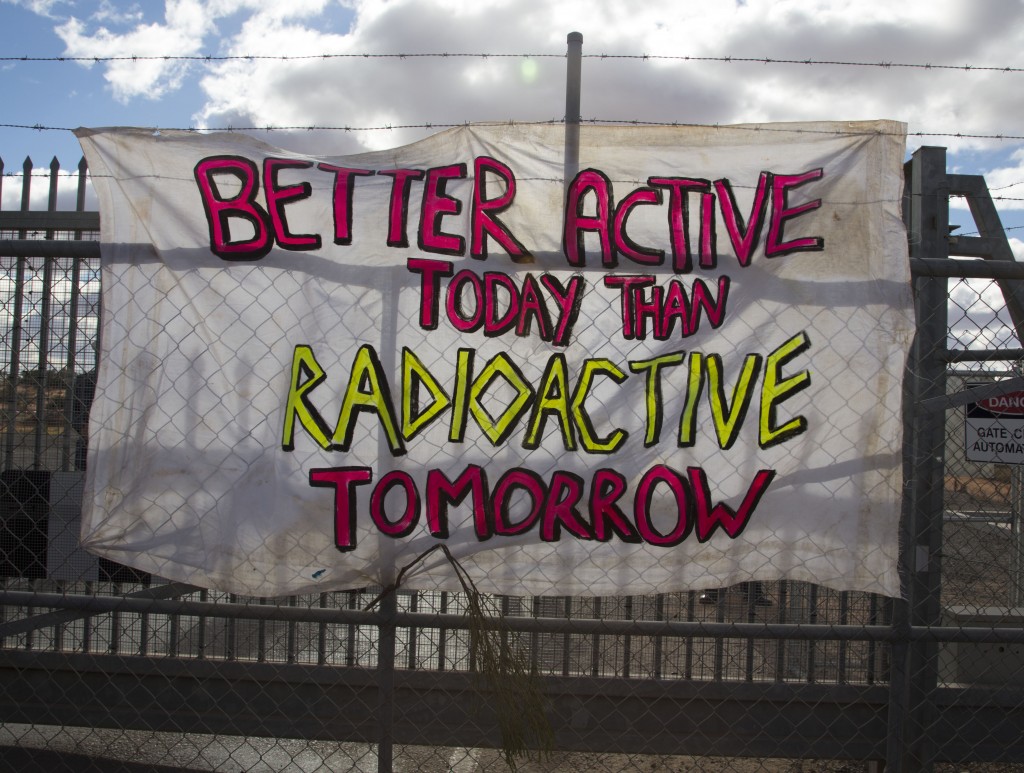

In November 2010, the Rum Jungle South Recreation Reserve was closed due to low-level radiation in the area. The Department of Resources said tests at the waste rock pile at the reserve detected low-level radiation. It advised the local council to shut down the reserve as a precautionary measure. The Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist was tasked with carrying out a comprehensive assessment of the site. (Click here and here for more information.)

On 7 October 2009, the Commonwealth and Northern Territory Governments entered into a four-year $7.05 million National Partnership Agreement on the management of the former Rum Jungle Mine site. The purpose is to undertake various studies to inform the development of an updated rehabilitation strategy, which may then lead to future rehabilitation works under new arrangements.

In other words, the saga of environmental pollution at Rum Jungle continues, 41 years (and counting) after the closure of the mine in 1971.

RECENT MINING NEAR RUM JUNGLE

In the 2000s, Compass Resources pursued plans to mine copper, cobalt, nickel, lead and silver near Rum Jungle (and near the town of Batchelor). Compass acknowledged that it was also interested in mining uranium at the nearby Rum Jungle site, over which it held a lease, including the Mount Fitch resource estimated at 4050 tonnes U3O8. Compass commissioned the Browns Oxide mine − about 1 km west of the former Rum Jungle complex − to mine cobalt, nickel and copper mining. The first shipment of copper left the mine in October 2008. But costs had blown out, cash had run out, the company was placed under administration in January 2009 and the Browns Oxide mine was put under care and maintenance (see Friends of Compass Resources and The Australian.) In May 2009, a decision was made to liquidate Compass Mining and place Compass Resources under a Deed of Company Arrangement.

Chinese company HNC (Australia) Resources proposed to develop the Area 55 Oxide Project to mine copper, cobalt and nickel and to process it at the nearby Browns Oxide plant. HNC also had an interest in restarting mining at Browns Oxide (it previously had a Joint Venture agreement with Compass). Those plans hit hurdles but may yet be revived.

UPDATES:

Radiation hot spots at NT lake

Northern Territory News, 3 December 2012, by Alison Bevege

http://aap.newscentre.com.au/acf/121204/library/nuclear_issues/30004975.html

RADIATION hot spots many times higher than background levels were found at a popular recreational lake downstream from one of Australia’s worst polluting mines yesterday.

Monash University senior environmental engineering lecturer Gavin Mudd found radiation levels as high as four microsieverts in spots around the carpark and barbecue areas of Rum Jungle Lake near Batchelor, 100km south of Darwin.

School children come on excursions to the lake for canoeing and kayaking while locals use it for swimming and relaxing.

Dr Mudd said the background radiation level was 0.1 microsievert. A conventional chest X-ray is 20 microsieverts according to the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation. Dr Mudd, who was testing the site with a geiger counter for the Environment Centre NT, said there was no immediate risk to the public but the site might need warning signs. “It wouldn’t be exposing the public to the limits in a couple of hours … but it is significant,” he said.

The lake was closed for 18 months as a precaution but re-opened in September.

Batchelor resident Bruce Jones, 70, often swims in the lake and said he was not worried. “We’ve got a letter saying it’s all OK out here,” he said. “They’ve opened it to swimming and the kids are coming from all the schools.”

Uranium was mined by the Federal Government at Rum Jungle from 1952 until 1971.

It did not clean up the site until 1983, but the clay covers put on the tailings heaps failed soon after being installed. Heavy metals and uranium have been leaking out ever since.

In September, the NT Government called for tenders for a new cover design to contain leaking.

———–

Clean-up not on federal agenda

NT News, 11 Dec 2012

THE Federal Government has refused to commit to fixing radiation pollution it left in the Northern Territory after mining uranium at Rum Jungle. Radiation levels are so high that camping has been banned at the nearby Rum Jungle recreational lake for public health reasons. The lake is popular with school excursions and is considered safe for day trips, including kayaking and swimming.

The Federal Government began mining uranium in 1953 near Batchelor, 100km south of Darwin, for use by the UK and the UK in nuclear weapons and for research. Mining ceased in 1971, leaving one of the worst polluting legacy mines in the Territory. In the 1980s efforts made to clean up the site failed.

A four-year study of the site is due to end in June. But the Federal Government has refused to commit to fixing the site once the study is complete. Resources and Energy Minister Martin Ferguson refused to commit to spending the estimated $100 million needed to clean up the site when questioned by the NT News.

Shadow Environment Minister Greg Hunt also refused to commit to action should the Coalition be voted in at the next election. “We will await the outcome of that report before making a commitment,” Mr Hunt said.

MORE INFORMATION:

Articles about pollution and rehabilitation:

- Mudd, G M & Patterson, J, 2010, ‘Continuing Pollution From the Rum Jungle U-Cu Project: A Critical Evaluation of Environmental Monitoring and Rehabilitation’. Environmental Pollution, 158 (5), pp 1252-1260. Available from Gavin.Mudd@monash.edu

- Taylor, G., Spain, A., Nefiodovas, A., Timms, G., Kuznetsov, V., Bennett, J. (2003), “Determination of the reasons for deterioration of the Rum Jungle waste rock cover”. Australian Centre for Mining Environmental Research, http://www.inap.com.au/public_downloads/Research_Projects/Rum_Jungle_Report.pdf

- Mudd, G M, 2000, Remediation of Uranium Mill Tailings Wastes in Australia : A Critical Review. Proc. “2000 Contaminated Sites Remediation Conference”, CSIRO Centre for Groundwater Studies, Melbourne, VIC, December 4-8, 2000, Vol. 2, pp 777-784, http://users.monash.edu.au/~gmudd/files/2000-ContSites-UMillTailings.pdf

[This webpage last updated September 2012.]

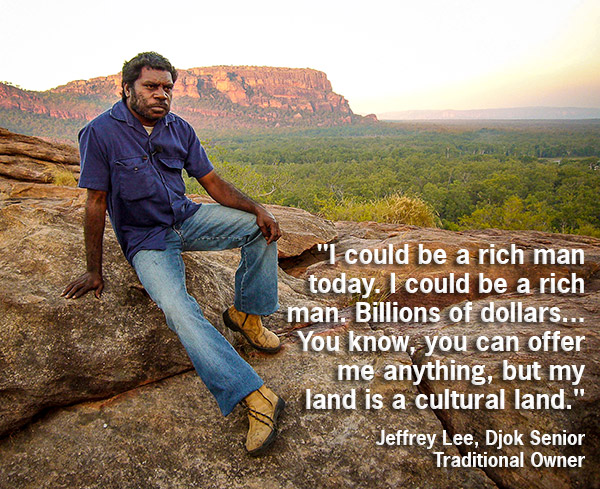

Senior Mirarr Traditional Owner Yvonne Margarula with friends.

Senior Mirarr Traditional Owner Yvonne Margarula with friends.

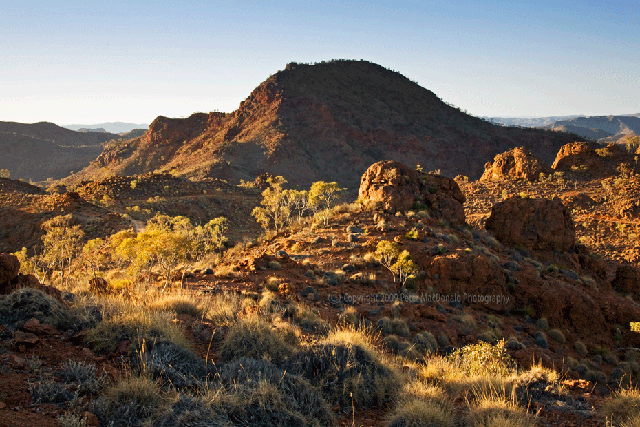

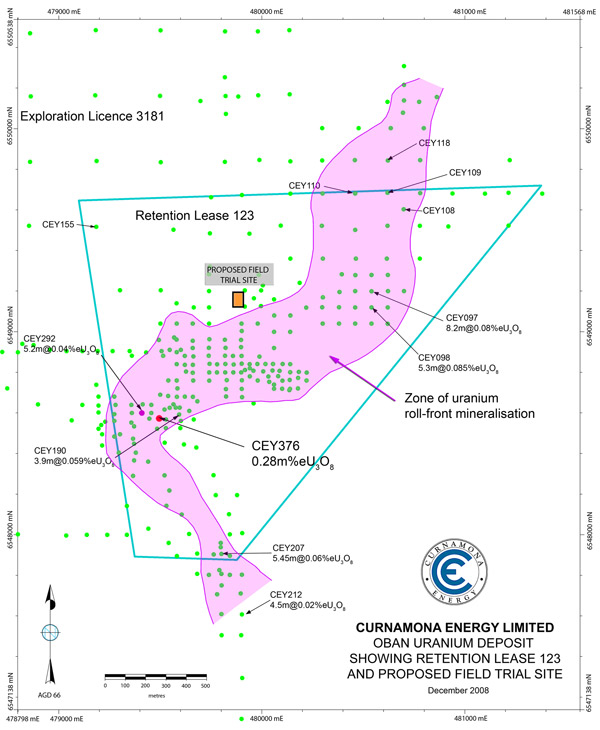

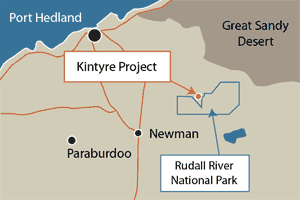

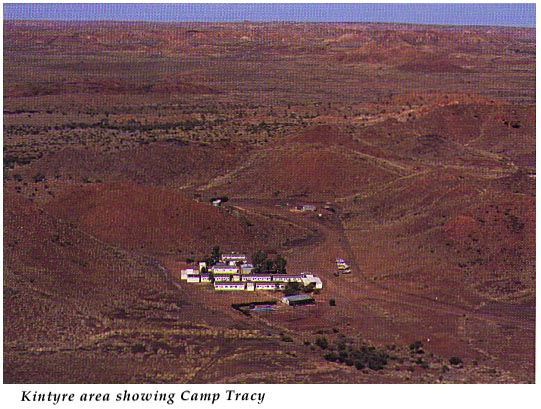

The deposit was discovered by Rio Tinto Exploration in 1985. From 1985-88, exploration by Rio Tinto identified eight deposits at Kintyre. In 1988 the project was put into care and maintenance due to low uranium prices.

The deposit was discovered by Rio Tinto Exploration in 1985. From 1985-88, exploration by Rio Tinto identified eight deposits at Kintyre. In 1988 the project was put into care and maintenance due to low uranium prices.