Adnyamathanha Traditional Owners Heather Stuart, Enice Marsh and Regina McKenzie.

Proposed national nuclear waste dump

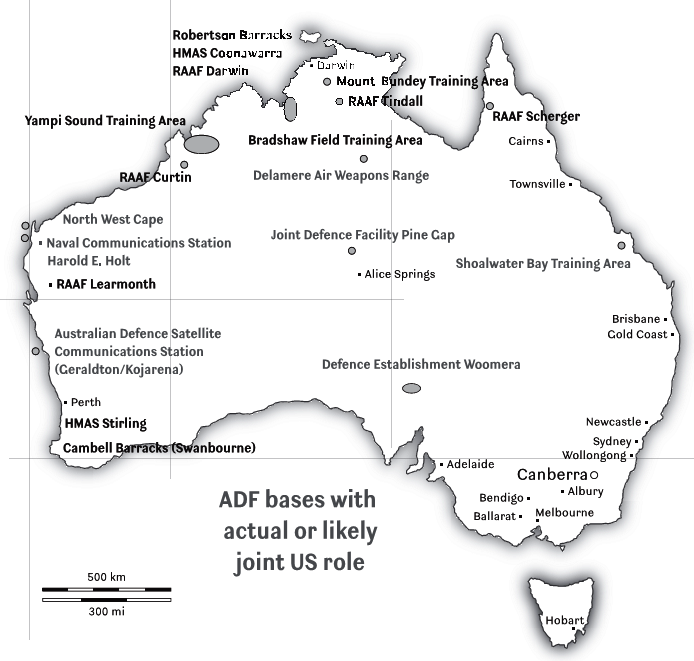

After the plan to build a national radioactive waste dump in the NT was abandoned in June 2014, the Australian Federal Government called for site nominations from across the country. There was no requirement for landholders to consult with or gain consent from Traditional Owners, neighbours or the broader local community.

From twenty-eight nominations received and accepted, a shortlist of six was announced in November 2015. The sites were Hale (NT), Oman Ama (Qld), Hill End (NSW), Cortlinye and Pinkawillinie (Kimba, SA) and Barndioota (Flinders Ranges, SA).

After launching campaigns in each area, representatives from the communities linked up to develop a coordinated response. A joint lobbying trip to Canberra was undertaken, which generated significant media and political attention and solidified friendships across the affected areas.

In April 2016, former Minister Josh Frydenberg announced that only one site was to be further pursued for the national radioactive waste facility ‒ Barndioota in the Flinders Ranges (SA). More recently, two others sites in SA ‒ both in Kimba ‒ were added so three sites are under consideration as of January 2019.

Adnyamathanha Traditional Owners were devastated to hear the news, with Elder Enice Marsh stating she was ‘shattered’ by the decision. Traditional Owner and neighbouring landholder Regina McKenzie said “We don’t want a nuclear waste dump here on our country and worry that if the waste comes here it will harm our environment and muda, our lore, our creation.”

Representatives from the other nominated communities released a statement offering ongoing support to their friends at the Barndioota site, stating they “stand shoulder to shoulder” with the community and “will offer whatever support [they] can.”

The nominated site is located adjacent to Yappala Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) and contains thousands of cultural artefacts. The country’s first registered storyline travels through right through the targeted area.

The community has built a strong local campaign, holding events in the nearby towns of Quorn and Hawker and developing a vibrant online and social media presence. Representatives have travelled to Adelaide, Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne to meet with politicians, conduct media interviews and speak at public events.

Supporters across the country have continued to build on the lessons of the Irati Wanti (SA) and Muckaty (NT) campaigns in supporting Adnyamathanha people and the broader community near the Flinders site. Networks have also been reactivated with key allies ‒ such as trade unions and health groups ‒ quickly stepping up to support the campaign.

For over two decades there has been a search for a single remote site to build a national facility. Targeted communities, key national environment and health groups and many trade unions have called for a new approach in the form of an independent inquiry into radioactive waste production and management that looks at a broader range of options and includes all stakeholder voices.

As of January 2019, Adnyamathanha Traditional Owners (through the Adnyamathanha Traditional Lands Association) are pursuing legal action, launched in December 2018, to try to stop the dump. Barngarla Traditional Owners are also pursuing legal action to try to stop the proposed dump sites in Kimba.

More information:

Fight to Stop Nuclear Waste Dump in Flinders Ranges SA

Federal government lies and racist propaganda

Videos: Beyond Nuclear Initiative

[This web-page last updated January 2019.]