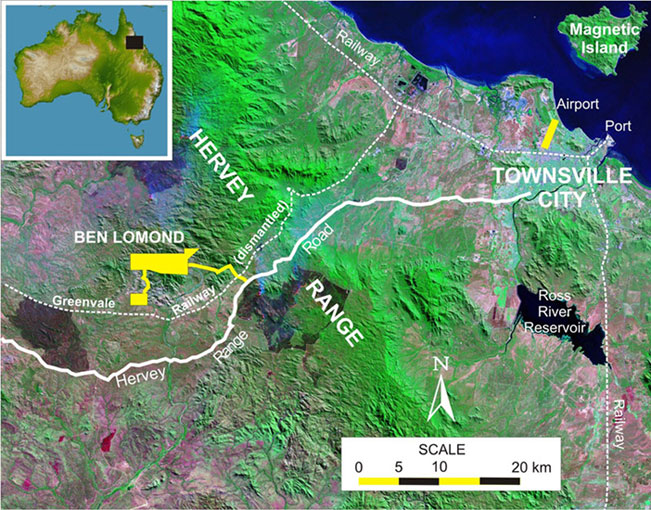

The Ben Lomond uranium (and molybdenum) deposit is located 50 kms west of Townsville. It is owned by Mega Uranium, which purchased it in 2005. The deposit is estimated to contain an estimated 4760−6800 tonnes U3O8 (for comparison, BHP Billiton plans to mine three times that amount of uranium annually at Olympic Dam in SA). If the mine proceeds, it will likely be a combination of open-cut and underground mining.

As of May 2012, Mega Uranium was undertaking prefeasibility studies with a view to determining the project economics, the preferred mining and processing options and the key steps in mine development. The recently-elected Liberal National Party state government has thus far maintained previous government policy of banning uranium mining, but Mega Uranium is betting on a change of policy.

The deposit was discovered in 1975 by the French company Pechiney, then explored and evaluated in detail between 1976 and 1982 by associated companies Total Mining and Minatome. In addition to problems with the Queensland state government, plans to mine Ben Lomond came unstuck because of federal Labor’s ‘three uranium mines’ policy from 1983 onwards.

Far-right pro-uranium federal MP Bob Katter had this to say in Parliament on 1 November 2005:

I present a serious note of warning to the House. Of the people in North Queensland that I represent, some 50,000 or 60,000 live on the watershed of the Burdekin River and draw their water from there. The honourable member for Herbert and the honourable member for Dawson are from there. The Burdekin Falls Dam provides water for some 210,000 people. These people are drinking water that comes from the lower reaches of the Burdekin River. The Ben Lomond uranium mine, 40 or 50 kilometres from Townsville, stands right above it. A French company—I think it was Aquitaine—proposed the development of that mine. I was very positive about it. I had been brought up and lived in Cloncurry, my hometown, beside Mary Kathleen. I knew all the people who lived there. I played football there. I went to church there. I did hundreds of things there. We had no evidence that indicated uranium mining was dangerous. Some greenies living up there—not a race of people that I like in any way, shape or form; but in those days there were some sensible people associated with them—started making a noise that there had been a spill of high-level radiation.

Whilst I have waxed lyrical about the dangers of uranium not being great, there is a limit to the dangers we will accept. In the case of Ben Lomond, the company said that there had been no spill. The government agency—the forebears of what we now call the Environmental Protection Agency—also said that there had been no spill. That was for the first three or four weeks. When further evidence was disclosed, they said, firstly, that there had been a spill but the level of radiation was not dangerous and, secondly, that it had not reached the water system from which 210,000 people drank.

For the next two or three weeks they held out with that story. Further evidence was produced in which they admitted that it had been a dangerous level. Yes, it was about 10,000 times higher than what the health agencies in Australia regarded as an acceptable level. After six weeks, we got rid of lie number 2. I think it was at about week 8 or week 12 when, as a state member of parliament, I insisted upon going up to the site. Just before I went up to the site, the company admitted—remember, it was not just the company but also the agency set up by the government to protect us who were telling lies—that the spill had reached the creek which ran into the Burdekin River, which provided the drinking water for 210,000 people. We had been told three sets of lies over a period of three months.

So I say to the people of the Northern Territory: make sure that ordinary people have some sort of oversighting mechanism. Do not leave it up to the government or its officials. They will dance to the tune played by whatever piper is in charge money-wise or politically. They will not answer to the tune of protecting the people. That has been my experience.

The case of Ben Lomond was notorious, and the very development oriented Bjelke-Petersen government said no to Ben Lomond. The most development oriented government in recent Australian history said no because of the absolutely outrageous performance of their own regulatory body, as well as the mine itself. One other humorous aspect, which was not really humorous at all, was when I asked the regulatory authority chief, ‘How do you get your water samples?’ He said, ‘We have them collected.’ I said, ‘Who do you have collect them?’ He said, without any guile, ‘The company.’ So we had the company protecting itself, not the people of Queensland or the people who were depending upon this water for their water supply.

Mudd provides a fascinating history of the attempted development of the mine from the 1970s onwards. A few highlights and lowlights from that history:

- The Queensland government’s eagerness to get the mine underway hinged on plans to site a uranium enrichment plant in Townsville − one proposal for which, at an estimated A$1000 million, came from Minatome in October 1979.

- Officially the Minatome lease was granted in early 1980 but, a year previously, the state Minister for Mines, Energy and Police, Ron Camm, announced that the mine would be given a quick go-ahead, in a statement made well in advance of completion of an Environmental Impact Study (EIS).

- Not only did the state government refuse to consult with the Townsville City Council and local shires (authorities), it also altered the Mining Act, thus allowing its Mines Department to over-rule local authorities, and it doctored procedures for conducting EIS’s − by dropping the term “Environmental” from the rules.

- Local surveys showed a majority of residents opposed to the project; and there had already been an anti-uranium march, in spite of the state’s draconian ban on all such demonstrations.

- From this point on, opposition mounted dramatically. The Australian Telecommunications Employees Association in February 1981 imposed communications bans on Minatome. The Movement Against Uranium Mining (MAUM) also announced a “tent village” at Ben Lomond, to be held that summer.

- The opponents’ case depended not only on previous experience in the uranium industry, but Minatome’s existing practice at the mine site. The Queensland Campaign Against Nuclear Power claimed that: “Already a level of radioactivity two and a half times the legally permitted level has been recorded in a creek which flows into the river. This was from a stockpile of 3500 tonnes. When the mine is in operation, the stockpile will be two and a half million tonnes.”

- Neil Heinze, a local civil engineer, claimed that radioactive leakage was “certain” to occur from the site, while all artificial methods of containment were inadequate. Professor Frank Stacey, Professor of Applied Physics at the University of Queensland, predicted that inevitable radioactive leaking would pollute the Burdekin river system, especially as the proposed dam across the river would “ensure that heavy pollutants tend to accumulate in the reservoir and any area in which water from the reservoir is used, instead of being flushed out to sea”.

- The Queensland Mining Warden rejected Minatome’s application based on environmental considerations. He found that there was no proper long-term arrangement for the containment of tailings. He questioned the appropriateness of clay as a liner for the evaporation ponds and tailings dumps.

- The Queensland Mines Minister, Ivan Gibbs, sought to overturn the Warden’s decision. By this time, another scandal was in the news. The national news magazine National Times revealed that Minatome had destroyed several vital Aboriginal sites “in the past couple of months” including one possibly some 4,000 years old, “considered to be one of the most significant in North Queensland”. This site was bulldozed by the company to make way for an experimental evaporation pond.

- Another Aboriginal quarry site “considered to be unique in Australia” was also under threat by planned high-tension power lines and water pipes, while a sacred pool was threatened by nearby drilling. A confidential document obtained by the National Times revealed that Minatome had been aware of these Aboriginal sites since 1978 and was advised in an archaeological impact statement that they should be protected.

- Early the next year, Minatome flew out 36 tonnes of uranium ore from Ben Lomond to Noumea in New Caledonia, then on to France. The flight was organised to evade union bans at Townsville, as well as adverse publicity.

- A few months later, the World Bike Ride − antinuclear activists who had set out from Melbourne in March − set up an “Atom-Free” embassy at the mine site itself.

- Then, in mid-1983, the federal Australian government banned all uranium exports to France, in retaliation for France’s continued nuclear testing in the Pacific. In response, the company reportedly filled in the tailings dam and development work came to a halt.

- At the end of the year, the company finally published the environmental impact statement − a few days after the ALP government announced a ban on all new uranium mines, apart from Olympic Dam.

- Early in 1986 it was reported in the Australian Senate that the uranium ore stockpiled at Ben Lomond had been virtually abandoned, with a minimum of security precautions.

More information:

- Mega Uranium: http://www.megauranium.com/properties/australia/ben_lomond/

- http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/Australia_Mines/pmines.html

- Dr Gavin Mudd: http://web.archive.org/web/20060621235454/http://www.sea-us.org.au/no-way/benlomond.html

- Minatome, March 1983, Ben Lomond Project − Draft Environmental Impact Statement, Brisbane, Qld, Vol 1 and 2.